The American Dream, Kunsthalle Emden, Germany

Kunsthalle Emden Drents Museum, Assen – the Netherlands & the Kunsthalle, Emden – Germany 19-11-2017 – 27 May 2018

The exhibition The American Dream now being shown in Assen, the Netherlands and Emden, Germany, is a cooperative project whereby an attempt is being made to clarify ‘variants of realism’ and to demonstrate how the artists interpret ‘The American Dream’. The Drents Museum concentrates on American realism from 1945 to 1965, while Kunsthalle Emden is primarily devoted to American realistic art from 1965 to the present.

After a visit to the Drents Museum in Assen (see review The American Dream 1) it was time to go to the Kunsthalle in Emden. Looking through the trees with their green leaves, a brightly lit arrow on the façade of the museum lit up, almost beckoning us to come in. This is the place to be, it seemed to say, and indeed, it was. The entire exhibition will be a wake-up-call for many, including for Americans themselves, as realism as an art form has taken second place on the American art scene to abstract expressionism.

The curators have prepared visitors well with an excellent introduction to the show by selecting several works which serve as guideposts to the exhibition as a whole. The choice of Edward Hopper (1882-1967) and Andrew Wyeth (1917-2009) as the primary representatives of American realism was made with the recognition their works provide a standard upon which to view the exhibition as a whole. With their realistic work they stand out against abstract expressionism, photography, photorealism and hyperrealism.

Hopper and Wyeth: light

In the first gallery Hopper Hopper is represented by his ‘Girl at a Sewing Machine’ (1921) and Wyeth by ‘Blue Door’ (1952) and ‘Lovers Study’ (1981). Both artists have placed their figures in natural sunlight shining through a window with accompanying shadows. Hopper’s light is subdued, whereas Wyeth’s is sometimes extremely bright.

The girl in Hopper’s painting ‘Girl at a Sewing Machine’ seems to be completely absorbed by her sewing, while Wyeth’s nude woman in ‘Lovers Study’ is obviously posing for the artist who shows details like the light stroking her pubic hair and thighs and part of her left ear sticking out through her tight braids. Hopper, with a touch of impressionism, concentrates on form, while Wyeth shows a different kind of precision and explicitness. Both paintings are fabulous, especially as they implicitly seem to tell us something about their makers.

Wyeth’s painting, ‘Blue Door’, approaches abstract expressionism, but it remains a realistic door reflecting sunlight from a nearby window in a ramshackle barn. Here the sunlight is quite dim when compared to ‘Lovers Study’. The light falls against the door and woodwork in varying shades of blue. The place seems to be cold and gloomy, yet we want to be there. The window within the brownish sill must be hard to open. Yet, this is exactly what we want to do. We almost feel the wind and hear the wooden floor creak. It is the intimacy of the barn that draws us in.

Both Wyeth and Hopper want us to recognize what they are depicting, although their work is mysterious at the same time. They share a love for the cinema, which often shows in Hopper’s work where we view a frame, as it were, from a film strip. These picture frames are often interpreted in terms of such moods as alienation and loneliness.

Larry Rivers

The introductory room further includes work by Larry Rivers, John French Sloan, John Koch and Charles Steeler. Larry Rivers’ work (1923-2003) is considered to be a bridge between Abstract Expressionism and Pop Art. His ‘Double Portrait of Berdie’ is an early work not yet reflecting his venture into Pop Art. This painting was regarded by some as a ‘shocking female portrait’. He was criticized for ‘his crude depiction of his aging mother-in-law’. She sits and stands by a bed with vaguely flowery sheets, her big hallux valgus toes sticking out and growing over the other toes. It is a realistic and somewhat impressionistic depiction of a naked older woman. Not shocking now, but at the time apparently it was.

According to Andy Warhol, ‘Larry’s painting style was unique and it wasn’t Abstract Expressionism and it wasn’t Pop Art. It fell into a period in-between. But his personality was very Pop’. Warhol also said Rivers was ‘the daddy of ‘Pop Art’ and called him ‘so chic’. The inspiration worked both ways, for Rivers had encouraged Warhol to paint everyday commercial objects. Don’t we all know Warhol’s vague representation of a camel on the Camel cigarette packet?

City Life: order and chaos

In connection with the exhibition John Koch: Painting a New York Life, Grady Turner says in an essay for the New-York Historical Society that ‘there is a studied informality’ to ‘The Forbes Family Portrait’ (1956) by John Koch (1909-1978). The family, two parents with their four children, are on their patio at the side of their swimming pool on what apparently is a cloudy day as there are no shadows to be seen. With respect to this oil-based painting, the modernist Koch explains ‘what is more important than whether there is or is not someone posing for you is the relationship between them’.

What is it then? At first sight the painting looks like a photograph with a very serious family gazing in the lens, the mother even appearing quite anxious. They all seem to be so organized, so quiet. No children’s chattering, no stains or spots, no smiles, no interaction. Both literally and figuratively, there are no ripples in the water. Is this why this intriguing and detailed painting also makes us feel slightly uncomfortable? His pictures celebrate refinement—of material, of craftsmanship, of manners and, so far as a silent art can do so, of social speech”. This work by Koch leads us to work by the artist Edward Melcarth (1914-1972) who was friends with Malcolm Forbes. Moreover, Forbes was apparently his benefactor.

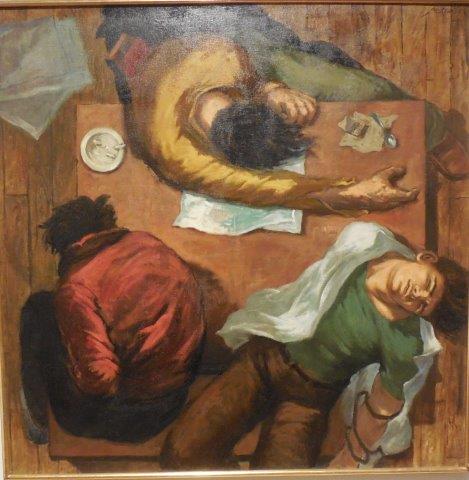

One could easily say that Melcarth was the antithesis of The American Dream, when it comes to sexuality and politics. He was an explicit homosexual and his adherence to Communism was accompanied by a ‘sensitive, emotional and heroic portrayal of the male working class figure’. His painting, called ‘Private Worlds’ (no date), depicts three men splayed out over the table, probably after having taken drugs. On the table are a teaspoon and an open pocket match box. They look exhausted and disheveled and we can see only one man’s face. He has his eyes closed and actually looks like a boy, which makes the scene even more disconcerting. We see the young men in their colorful t-shirts from above: a panoramic view, a form which is often used to zoom in on beauty, thus reinforcing the focus on quite another side of city life.

E. Melcarth, Private Worlds

The room, entitled City Life, also includes four small rectangular oil-on-canvas paintings by Dee Shapiro (1936 – ), which present an overview of a city under the title, amongst others, ‘View from White Street’ (2000).

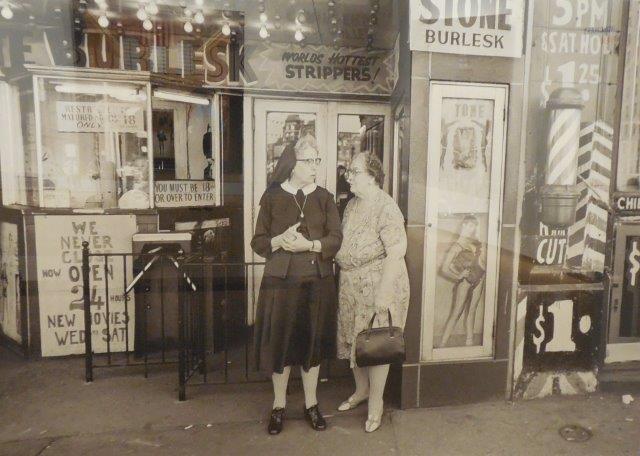

City Life is also a theme of the photographer Bill Rauhauser (1956) in depicting life in his home town of Detroit. In one of the eight photographs, ‘Stone Burlesk’ (1960), a nun and a rather plump woman with a very low bosom, a stiff handbag and very practical shoes are standing before strip joint entitled, Stone Burlesk. They stand out against a background with the phrases ‘World’s Hottest Strippers’ and ‘you must be 18 or over to enter’. We cannot help smiling.

B. Rauhauser, Stone Burlesk

The City Life room of the show also focuses on such urban photorealist artists as Latvian-American Vija Celmins’(1938 – ) ‘Tulip Car’ (1966), ‘Scotton Inn’ by Robert Kniewek (1951- ), ‘A Bend in the Road’ (2003/04) by Stone Roberts, ‘Potrero Golf Legacy’ (2012) by Robert Bechtle, ‘116th Street’ (1992) by Daniel Greene (1934-), ‘Saturday Evening: Summer’ (2009) by John Moore (1941 – ), ‘Coffee’ by Max Ferguson (1959 – ) and a photorealism picture of a movie theatre featuring the film ‘Goodbye, Norma Jean’ entitled ‘Martin Theatre, Harrison Avenue, Panama City Florida (1976) by Stephen Shore (1947 – ). Shore’s work is a chromogenic color print.

Countryside

Moving to the Countryside Gallery there are six oil-on-canvas works, one in acrylic, one in chromogenic print and one in gelatin silver. Kurt Knoblesdorf’s (1979 – ) oil, entitled ‘Naval Yard’ (2009), appears to be a tottering two-story white house with a brownish colored roof over a long front porch. The object is set with a dark blue sky background, a lone tree to its side and a dark yard in front. Robert Birmelin’s (1933 – ) ‘Metaphysical Rock Group’ (1970) is a rock-covered beach on a lake which fades into a hilly horizon on the other side and a hazy sky.

Neil Gavin Welliver’s (1929-2005) ‘Snow on Alden Brook’ (1983) shows a small stream, a lot of snow, both depicted by strong brushstrokes and subtle dollops of paint, brownish trees trunks cutting through all of this whiteness. Welliver had begun by painting nature as directly observed. Later he says about his paintings of the Maine woods that it was ‘not light in the normal sense, light bathing objects, but light in the air, flashing and moving like a flow of energy through space’ and that this is what his paintings are about.

Intriguing

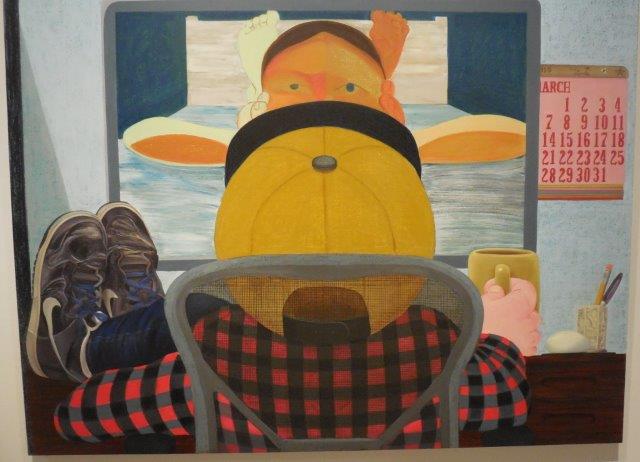

Nicole Eisenman (1965 – ) presents us with an intriguing ‘Long Distance’ (2015), a work which keeps us talking as to what is going on. We see two figures, one looking at the other who is looking back from a screen. The one we see from the back is wearing a red and black hunter’s shirt and tennis shoes plus a baseball cap, feet with sneakers on the table on the left of the screen, while the right hand is holding a mug. We only see the eyes, hair and feet of the other person, who is apparently lying on a bed. Boy – girl? Girl – boy? Two boys? Two girls? The suggestion is that this could be anybody: us, our children, our neighbors. The screen in the middle of the painting is like a frame within a frame, almost like a prison. Form and content seem to reinforce each other and breathe a sense of loneliness, almost as if to say: is this how we communicate?

N. Eisenman, Long Distance

In the hyper-realistic work ‘Market Basket Harley’ (2007) by Tom Blackwell (1938), we see a Milwaukee-made Harley Davidson in all its glory standing idly aside a sign announcing a number of food products such as pizzas, gourmet foods and organics.

Blackwell says: ‘I have discovered that translating the image from the photograph requires the most intense discipline and that limiting the arena of self-expression also refines it…the photograph is a tool which enables me to freeze the ‘ordinariness’ I am after, one which helps me to achieve the veracity that makes it possible to capture the ineffable in the commonplace’. Blackwell says he is devoted to the total appropriation of the object, in this case the motorcycle. This is a protest against those artists who are satisfied with a partial presentation of the object.

Genre and still life

Moving on to the room, named Genre, we have a work in pencil entitled ‘Hillary Clinton’ (2016) by Karl Haendel (1976). It is a huge photorealistic portrait (261 by 434.3 cm) of the recent presidential candidate in what seems to be a somewhat perturbed mood.

It cannot be a coincidence that, further in Genre, Peter Saul’s (1934 – ) ‘Quak-Quak, Trump’(2017), a portrait of the current president, is on the opposite wall: a huge, cartoon-like setting (198.1 by 304.8 cm) together with surrealistic duck-like heads sprouting out of a floating hamburger with boxing gloves, hitting Trump’s head. There are also a few little ducks squirming in his voluminous hair that he tries to shoot. Sometimes successfully, considering the blood drops splashing around.

In the Still Life category, the Emden Kunsthalle rooms exhibit ten American artists with heavy concentration on new artistic styles of photorealism and hyperrealism, developed during and after the 1960s. Charles Bell (1935-1995), for instance, is represented by his hyper-realistic pastel ‘Before the Journal’ (1986). In sharp detail, he shows three cartoon-like figures – a monkey in costume on a tricycle, a toy clown on a wooden horse and another dressed-up monkey on a red toy car. Further, the hyper-realist work ‘Queen’ (1976) by Audrey Flack (1931 – ) is enamored by odds and ends sitting on a dressing table. She uses acrylic paint to show in richer than life colors, among others, a locket, a chess piece, a rose, the queen from a deck of cards, an old-fashioned pocket watch and a slice of an orange.

Few if any kiosks are so neatly stacked as Ken Keeley’s ‘Newsstand’ (1989). Keeley (1946 – ), which displays magazines, newspapers, candy bars, lottery tickets, each particular item clearly shown for all to see, included – of course – The New York Daily News, The New Yorker Magazine, Forbes Magazine and Life Magazine with a full page picture of the actor Clark Cable starring in ‘Gone with the Wind’.

Hyperrealism, partially because Abstract Expression shows little and impressionism only suggestively so, is an attempt to make everything absolutely clear – not merely to imply or infer. Ralph Goings’ ‘A1 Sauce’ (1995) is a good example of this style, especially because it portrays an everyday meal’s consummation product.

Catalogue

The catalogue also includes two oil paintings by Alice Neel (1900-1984), a portrait of Raphael Soyer (1970) shown in Assen, and a still-life ‘Black Bottles’ (1977) at Emden. The still-life is limited to wine bottles together with a bowl of apples sitting on a tannin-colored table top in a fragment of a white-colored room and hallway all set off by a reddish floor. The still-life is somewhat of an anomaly as the greater part of Neel’s oeuvre consists of portraits. At first she concentrated on nude females and later in her career on personalities she encountered in Greenwich Village and Harlem in New York. Not only are her portraits characterized as possessing an ‘intense humanity’, but also, according to Victoria Miro in The Guardian, ’a unique window on the changing world in Harlem in the years before and after civil rights’. She provided us, says Miro,‘with a true picture of urban life in Manhattan’.

A not too minor criticism with respect to the catalogue is the failure to provide page numbers of paintings by the artists in the index.

Time to relax

Last but certainly not least, the Tiffany Lounge with its reading table, glass lamps, special Tiffany windows, art-deco chairs, sherry glasses almost tempted us to pick up one of the books and relax. However, it was not until we entered the diner that we took time to catch our breath. We sat down on the red-white seats at a white table with silver chrome legs, while watching films about feminism and other movements in the 1960s and 1970s.

The timeline on the wall is not only accurate, but also looks playful and appealing because of its form. Protruding wooden blocks with historic events written on them, all ‘hanging’ on blue stripes of paint on the wall, tell us all about the development of The American Dream.

Inviting

The exhibition is an excellent introduction to American Realism. Although some aspects of American realist paintings have been omitted such as Precisionism, we are presented with a general overview from Impressionism to Regionalism, Social Realism, Abstract Expressionism and Pop Art and lots of other art forms.

The arrow on the facade of Kunsthalle Emden, inviting you in for The American Dream, will not be there for much longer, but there is still a quite astounding permanent collection.