Museum Voorlinden, Wassenaar

9 June 2018 – 28 October 2018

The works of Wayne Thiebaud (b. 15 November 1920) were vaguely familiar to us given his inclusion in an exhibition on American realist painters at the Emden Kunsthalle earlier this year. Consequently, we had some notion as to what to expect when about to cover a first European retrospective of Thiebaud’s works at Museum Voorlinden in Wassenaar, South Holland. Upon entering the exhibition at the beautifully designed museum we were struck by his seemingly ordinary paintings of cakes, pies, ice cream cones and hot dogs.

But then upon closer scrutiny we were surprised to see a great variety of colors in thick blotches of paint making up the objects on display. Also, curiously enough, the cakes, pies, etc. were painted, as it were, in isolation. An ice cream cone all by itself, or lonely hot dogs. Pastries were either placed on an isolated shelf or in a singular case, leaving it up to your imagination as to their actual location. In addition, Thiebaud’s pastry objects exuded the use of heavy pigment, exaggerated colors and shadows.

Pop Art or not?

In fact, Thiebaud says he was drawn to these objects precisely because they were commercially made, as if they were off the production line. But pastry objects were not his first ambition. He began drawing when in his teens. At the time he largely drew cartoons and illustrations. He also made posters for theaters, was taken on as an apprentice at Disney Studios and In 1942 he enlisted in the U.S. Air Force where he worked as an artist in the special services unit.

After the war, he was employed to paint images for signs as well as to create a special design for license plates that were used by the State of California to raise extra revenue. The style adopted by Thiebaud in the 1940s resembled abstract expressionism, illustrated by the extremely large mural he made for the Sacramento Municipal Utilities Distribution Building (250 feet long and 15 feet high). The mural drew attention precisely because of its similarity to a work of abstract expressionism. Meanwhile, in his mid-20s Thiebaud travelled to New York where he obtained work as a free-lance cartoonist.

Upon returning to California one year later he enrolled in San Jose State College and subsequently at the California State University at Davis in Sacramento, California where he remained as a teacher until 1991. He returned to New York some ten years later in 1956 where he became friends or acquaintances with some of the great exponents of abstract expressionism such as Willem de Kooning, Fritz Kline, Rauschburg and Jasper Johns.

At an exhibition held by the Allen Stone Gallery in New York, he also had the opportunity to join what is now known as the Pop Art group, including the Pop Art artist of great repute, Andy Warhol. As a result of Thiebaud’s participation in this exhibition he was, at first, identified as a member of the Pop Art school of art. This, however, was not the case. What was Thiebaud’s opinion on the dominant abstract expressionism as exemplified by De Kooning and Pollock? According to a quotation from Thiebaud in an article by Ian Parker in The New Yorker: ‘ I’d been painting like De Kooning and Pollock, and trying to make it look like art. You develop those convenient signs of art – the drip, or whatever those things use’.

Haloes

But why are pastry objects of such fascination to Thiebaud? In several interviews Thiebaud tells of his experience growing up in Long Beach, California. He used to stop in front of a pastry shop while walking near home and gaze at the delicious-looking cakes, donuts and pies. Moreover, aside from this inspiration, Thiebaud became more interested not so much in these objects as such but rather in how he could portray them on a canvas. Through experimentation, he discovered that by providing the objects with an external halo of paint the relationship of the different paints would actually seem to vibrate.

Thiebaud applied the paint in such a way that the texture actually resembles thick cream, smooth frosting and streaks of mustard. His own term for this is ‘object transference’. He has no cakes or pastry in his studio and paints them from imagination and memory.

But what did Thiebaud believe was his true style? In a quotation from an article in another New Yorker article this time by Rose Glaser Friedrick, Thiebaud says: ‘ I’m just essentially a traditional painter, and by that I mean, always interested in imagery, trying to make a representational painting that has as much abstraction as seems to fit that particular mode of representation’.

In a further definition of what Thiebaud believed he was doing, he told Martin Gaylord in the Apollo Magazine: ‘ I don’t have much to do with realism; there’s a big difference between realism and representation’. Taking a note from Willem de Kooning who described the style of Thiebaud from Thiebaud’s perspective: ‘I’ve got a wolf’s brush that makes terrific lines. That’s what you use, it all comes out of these’.

A sense of immediacy

We can better understand the purpose of Thiebaud’s halogens outlining his paintings by reviewing his figurative works for they, too, are activated, so to speak, by the application of lines of paint which give the work a sense of vibration and energy. Take, for instance, his portrait Robed Woman with Letter. The letter on the table top in front of the woman is ringed with a line of yellow paint. We know this is done in black on the occasion of death notices, but here it gives a sense of liveliness.

Moreover, even though the portrait is done straight on and the woman’s expression seems to be without a strong emotion, one has the feeling there is something personal going on here. But what is it? We feel her presence. Why are her arms straight down where you would expect them leaning on the table? Has the letter already been opened or not yet? The halogens around the letter and the table seem to give it all a sense of immediacy. Both people and objects seem to stick out against their backgrounds, thus almost coming alive. It is almost like poetry where unusual word combinations and metaphors stir images in its readers.

Here, observing Thiebaud’s work, we sense a certain rhythm in Thiebaud’s paintings, an atmosphere, a whole world behind them. We are aware that something must have happened just before we approached the scene, which makes us almost like priers. It is as if we were not supposed to be here. Yet, we stare and gaze.

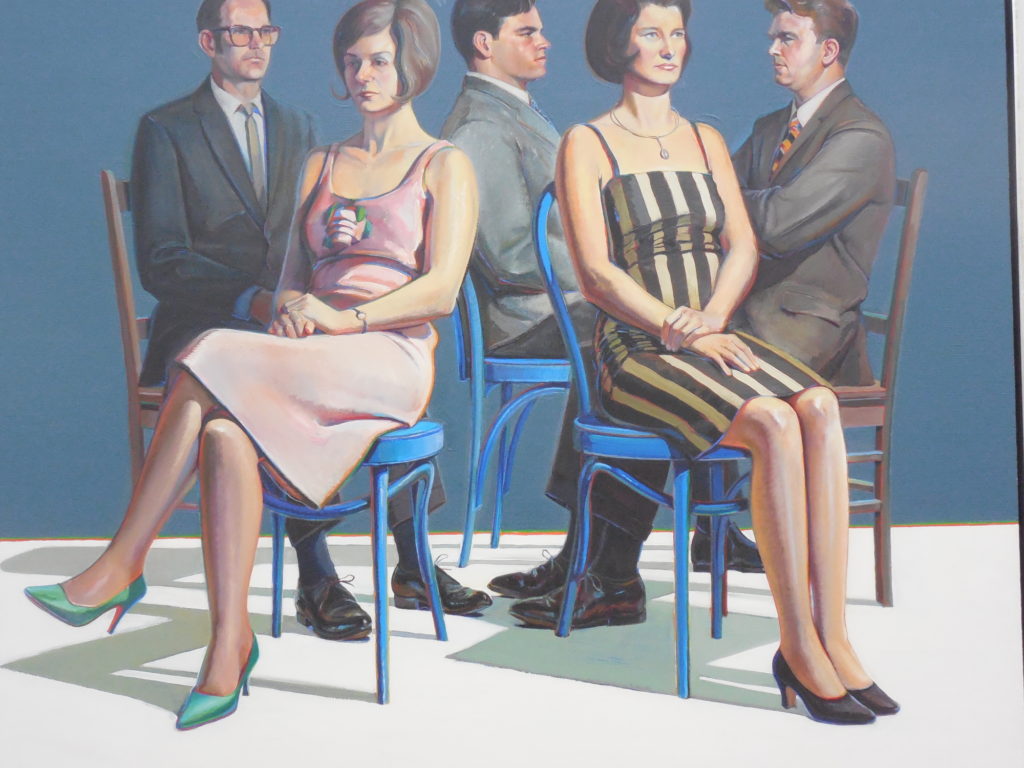

Why are the two women and three men in Five Seated Figures (1965) in a circle without looking at one another? Two chairs are turned around completely. The whole group is wearing festive clothing, matching shoes, all shiny, and their hairdos look immaculate. But where is the party? Where are the drinks, the chatter, the laughter?

They are sitting stiffly on straight chairs with straight faces, hands resting in the lap and one man with his arms crossed. Are they angry? Something must have transpired and apparently it is something they cannot share. We happen to stumble upon them and what to do now? How long are they going to maintain their position? Obviously forever, but they seem so real that we are drawn into their lonely circle, at the same time feeling we should actually sneak away, apologizing for intruding.

Five Seated Figures

The same holds good for the almost life-size Standing Man (1964) who is dressed in a poor suit, at least two sizes too large and with two buttons, but only one button-hole. The shabby suit has been ironed, though, because there are no creases and the pants are neatly pleated. His skinny neck sticks out, his head is slightly tilted. He looks forlorn and uncomfortable with his hands dangling along his body. He is standing against a beige wall and on a beige floor, separated by a yellowish line.

His polished shoes, like the suit, are so large that you suspect the whole outfit has been lent to him. Apparently he needs it for a serious occasion. We want to know what is going on. We want to reach out instead of gawking at him and adding to his discomfort. This is the thing: the people in the paintings look alive, not only because of the colors, their shadows, the lines in the background, but also because we seem to catch them in the middle of a personal story.

The Girl with Ice Cream Cone (1963), as usual Thiebaud’s wife, in her bathing suit looks at us. She looks sexy, no doubt about that. At the same time she looks as if we are in her way as she was just enjoying her ice cream. We have entered this part of the beach that was hers just a moment ago. Her bathing suit, in a way, reinforces our sense of trespassing, for there are trees and hills on it, also between her legs which are slightly apart. Again, what is happening here? This is a painting and we can have a close look if we want to. It is in the museum for us. Yet, we almost feel as if we are imposing upon her.

Some people in the paintings make us laugh, for instance two men and a woman on the beach, faces down. Their position cannot be comfortable. They are wearing colorful bathing stuff, which suggest this is fun, but where are the towels? Are their faces in the sand? The people are grouped like the pies, ice creams, the hot dogs. Five Hot Dogs (1961) is even on the same wall, looking quite unappetizing with the mustard oozing out. Involuntarily, you compare these works and chuckle.

- Five Hot Dogs, 1961

- Three Prone Figures, 1961

A swaying street

When moving from the pastry and figurative still lifes to the cityscapes, the third category of Thiebaud’s work, we move back again to a form of abstract expressionism or even to a kind of realistic surrealism. Although we know these paintings depict a scene in San Francisco or an outlying area about the city, the resemblance on the basis of representational style is far-fetched. The street, for example, directly in the center of his Intersection Buildings (2000 – 2014) appears to be moving up just as if it were a bridge which has been raised as if to let ships go by. The strong colors, too, make the street almost sway.

The exhibition is the first Thiebaud retrospective in Europe and thanks must go to the work and passion of director Suzanne Swarts for enabling us to see this very unusual and fascinating artist, who – in his 90s – is still working and playing tennis. Vibrant in person, vibrant in his paintings.